For the Macedonian version of this article, click here.

The Macedonian people have yet to decide if they view ex-Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski as a monstrous anomaly of his party VMRO-DPMNE, or as its archetypal product. This chicken-egg dilemma will not be solved with any criminal investigation, or even with a legal verdict. To use Gruevski’s favorite phrase, its resolution is solely up to the people.

Less than two months after the transition of government in Macedonia, center-right DPMNE’s eleven years in power are mentioned almost solely within the context of the Special Public Prosecutor’s Office, an ad-hoc institution set up to deal with the multiple crime allegations that emerged out of a series of wiretapped conversations between former government officials. With most of the party leadership facing multiple years in prison, one might easily forget the more basic question: how could the last eleven years have happened? And were the signs of what would follow already obvious in 2006?

One way to answer this question is to locate the inception of the Gruevski era in a specific event. Those who once supported Gruevski often hurry to point their fingers to the Greek veto of 2008, when Greece vetoed Macedonia’s accession to NATO, as a turning point. It was exactly then that Macedonia’s dramatic and continuous backsliding according to most relevant democracy indexes began, which suggests that the government gave up on European integration, and began focusing its entire energy on ruthlessly cementing its power. This narrative implicitly exonerates those who voted for Gruevski during his first two election wins in 2006 and 2008 of all the dirt of the Gruevski era that would follow. It also implies that it was the international community that turned Gruevski from a pro-European reformist into a Balkan despot with its failure to apply sufficient pressure over Greece and avert the NATO veto.

While this argument is merely partly inaccurate, ascribing any explanatory power to it is extremely dangerous. The accurate part is that, by undermining Macedonia’s Euro-atlantic integration prospects, the Greek veto did deny Gruevski his sole incentive to govern democratically. Yet, what matters more is the dangerous part, which is that any relativisation of the Gruevski era vis-à-vis some unfavourable external circumstances merely vindicates the painful old stereotype of “Macedonian submissiveness”, or the ability to find an excuse for anyone, including for the man who destroyed a whole decade of your life.

However, even if one logically looks for an explanation of the Gruevski era within the Gruevski era itself, one is still faced with a choice between two opposed interpretations. Was this a bunch of immoral politicians who captured both their party and the state for personal profit? Or was it merely the most recent manifestation of an inherently undemocratic party which does not deserve a new chance to reform itself? By deconstructing the two chief foundations of DPMNE’s popularity throughout the years, this article proposes the latter interpretation.

Myth #1: VMRO-DPMNE is an adaptable party

In his first statement after he was elected party leader in 2003, Gruevski stated that “everything is directly or indirectly connected to the economy”. This sentence embodies the technocratic image which Gruevski was trying to advance with his young age, but above all with the relative political anonymity of his first cabinet as prime minister in 2006. The low approval ratings of the then opposition party SDSM warranted that the new government would define itself in opposition to its predecessor: as new and competent people who would simply do their job rather than “be politicians”. DPMNE would then reinforce this much desired contrast against SDSM by emphasizing its superior adaptability, which is to this date proudly espoused as a defining DPMNE characteristic.

While major SDSM officials Radmila Sekerinska and Branko Crvenkovski have over the years retained their party positions despite their election losses, DPMNE carried out a thorough restructuring of its leadership after its defeat in 2002. Hence, Gruevski’s years as opposition leader, as well as his first two years in power, have largely been remembered for their strong technocratic nature.

However, if one switches the focus of the analysis from the superficial replacement of DPMNE’s pre-2003 leadership with people loyal to Gruevski towards substantive change, one realises that DPMNE’s restructuring was neither democratic in 2003, nor could it be democratic today. One unambiguous warning against Gruevski’s authoritarian tendencies goes as far back as 2003, when Gruevski sabotaged a parliament session which had taken an unfavourable course for him by stealing parliamentary speaker Ljupco Jordanovski’s key card. Moreover, the rhetoric, behavior and background of Gruevski’s “reformist” cadres during his years as opposition leader was in close flirtation with nationalistic scaremongering, and worked sharply against his self-proclaimed technocratic image. For instance, one of his closest collaborators and later minister of foreign affairs Antonio Milososki was hardly technocratic, as he had not built his public reputation through professional achievements, but rather with his prominent participation in the exclusionary anti-Albanian protests of 1997.

Today, any restructuring of the party would have to start with those few party officials who have been untarnished by the wiretapped conversations mentioned above. Sadly, the democratic capacity demonstrated by some of them so far is hardly promising. Nikola Poposki, who is often mentioned as a possible future party leader, never found the courage to denounce or at least distance himself from the despicable party narrative in response to the wiretapping scandal of disputing the authenticity of the recorded conversations. On the contrary, Poposki was a fierce advocate of this narrative, including in his infamous interview for a foreign media outlet last year in which he clumsily tried to justify the behaviour of the party by arguing that “even the road to hell is paved with good intentions”. Then there is Vlatko Gjorcev, who headed one of DPMNE’s party lists in the 2016 elections, and who chose to attack the disunity within SDSM on LGBT rights in a recent TV debate on the topic rather than respond to the arguments of his colleagues, thus explicitly demonstrating how alien the concept of intra-party debate is to him.

Furthermore, DPMNE’s lack of democratic capacity was best confirmed by the newly formed Initiative for Reform within the party. Its representative Petar Bogojeski recently stated that one of the main things he holds against Gruevski is allowing DPMNE MPs to vote for the formation of the Special Public Prosecutor’s Office. Thus, Bogojeski implied that he was not bothered by the potential crimes committed by the party leadership, but rather by the fact that the leadership put themselves in a position to be held responsible. (On the same occasion, Bogojeski also said that those who believe in God have no reason to be afraid of earthquakes).

Myth #2: Macedonia = DPMNE

The recent transition of government in Macedonia was the long overdue outcome of the parliamentary elections of December 2016 won by DPMNE, albeit with a significantly narrower margin over SDSM than before. However, the severely anti-Albanian nature of DPMNE’s electoral campaign, as well as the burden of the wiretapped conversations, prompted the biggest ethnic Albanian party, DUI, to refuse to form a governing coalition with DPMNE and choose SDSM instead. Thus, with the new SDSM-led government being constantly portrayed by DPMNE as illegitimate and unreflective of the popular will, a long-term analysis of DPMNE’s own popular appeal is in order.

The premise behind the proposition that the survival of DPMNE stands at the very core of Macedonia’s democracy usually goes back to DPMNE’s victory in Macedonia’s founding elections of 1990, or immediately after the party was founded. What is often bracketed out, however, is that DPMNE actually suffered an overwhelming loss in the first election round to the discredited League of Communists of Macedonia (SKM-PDP), which was dissolved shortly afterwards. Even in the second round, second-best SKM-PDP and third-best Union of Reformist Forces won a combined 54% of the vote, as opposed to 30% for the winning DPMNE. Unlike in 1990, the left united around SDSM for the 1994 elections and won more than twice as many votes as DPMNE. Of all parliamentary elections ever held in Macedonia, including all of Gruevski’s five election wins, SDSM’s victory in 1994 is the most resounding election win in the history of the country.

Moreover, electoral turnout in any of the five elections won by DPMNE under Gruevski has been significantly lower not only compared to the turnout in 1994, but also in compaison to the 2002 elections (also won overwhelmingly by SDSM ). This further undermines the already eroded legitimacy of these victories after the harsh electoral manipulations documented in the wiretapped conversations. Thus, while it remains a fact that DPMNE has (one way or another) ruled Macedonia for fifteen out of a total of twenty-six years of independence, the election results of this party are nowhere near resounding enough for its survival to be tied with the survival of Macedonia’s democracy.

The Meciar of Мacedonia

Nonetheless, even some of DPMNE’s most vocal critics adopt the argument that the survival of the party as a democratic reflection of the popular will of hundreds of thousands of voters is desirable. Hence, if DPMNE was dissolved, these voters would find themselves fully excluded from the democratic processes, and might even support the formation of a new, much stronger (and more nationalistic) party built on DPMNE’s ruins.

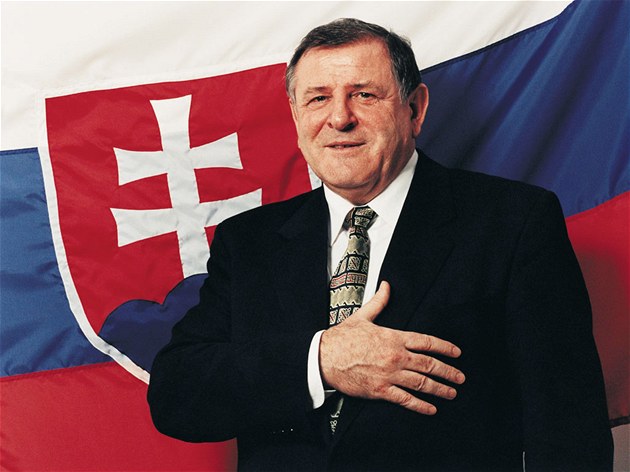

At the beginning of the 21st century, the intelligentsia in Slovakia probably shared these same fears. Ex-Prime Minister Vladimir Meciar, whose authoritarian rule from the 1990s bears an uncanny resemblance to the Gruevski era, kept winning elections in 1998 and 2002, but he could not form a government on either occasion due to his destroyed coalition potential. With the passing of time, but also as the judicial processes against him and his associates for multiple abuses of power progressed, his party HZDS was expressly relegated from the comfortable throne of a “defender of the Slovak people” to the electoral margins. In 2010, HZDS won 4% of the vote and was kept out of parliament; in 2012, it won a miserable 0.9%, and was dissolved forever in 2014. Naturally, the nomenklatura inside the party was so resistant to reform that Meciar remained party leader until its very dissolution, or nearly two decades after losing power in 1998.

Today, Meciar is still not behind bars, but the Slovak people could probably not care less about his personal destiny after they decided his political one a long time ago. Slovakia has been part of the European Union for 13 years. HZDS, on the other hand, is deep inside the dustbin of history, which is where DPMNE belongs as well.

This article was originally published in Macedonian at Respublika.

Pingback: Milana Travis