Two and half years ago, when I was informed that I received a scholarship to pursue my Bachelor’s degree in Germany, my whole family gathered to celebrate. It was ridiculous that, instead of wishing me to achieve even greater academic goals, most members of my broader family circle greeted me with the words “You should get married soon, so that we have a reason for another big fat celebration like this one.” This might have its roots in education, keeping in mind that only my parents have a university diploma, but it indubitably has a cultural background as well.

Since it was my family, I assumed they wished me all the best. But then I remembered the old Macedonian belief that women’s success can and should be measured by their marital status before their academic achievements. What infuriated me even more was that it came from a woman who got married at 19 and who has claimed many times that her husband prevented her from becoming an accomplished person. Macedonia has no official statistics on domestic violence of women, yet media often reports domestic violence, and some media houses even report a growing tendency.

Why would a woman that perceives marriage as being subordinate to her husband wish her granddaughter ‘all the best’ in such words? This was an even bigger question for me than the question why there is so much domestic violence, because the answer lies in the reasons for domestic violence.

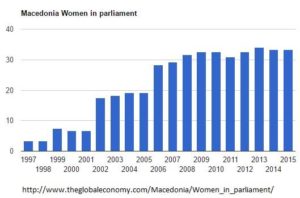

When it comes to participation of women in political institutions, Macedonia is a leader in the Balkans for women MPs with more than 30% women in the last parliamentary composition, but this can be also ascribed to a gender quota introduced in 2002 which prescribes that every party should have at least 30% women on their electoral lists . Therefore, the leap from almost no women to more than 30 MPs in 10 years should not come as a surprise. For the coming elections, the parties might aim at increasing the percentage to 40% to get closer to the European Union average. Yet, structural empowerment for women is only the starting point towards women’s emancipation and cannot combat tradition on its own.

One day during my summer break, I was at home and my grandmother interrupted me while I was reading in my room. “What are you doing?! Isn’t your boyfriend supposed to come any minute now?!” she yelled as if she had seen a ghost, and not a 21-year-old reading a book in her bed. “I’m learning Spanish, you know…” –“Ohhh Spanish! Get up immediately and clean the room! How is that guy ever going to want to marry you if he sees you lying on your bed while the room is a mess?” I tried to say something that made sense (at least in my mind): “You know grandma, Spanish is my 6th language, and marriage is not a thing I’m interested in as a 21-year-old…“. She interrupted me again: “Poor guy that has to cope with this kind of attitude and mess!”

One day during my summer break, I was at home and my grandmother interrupted me while I was reading in my room. “What are you doing?! Isn’t your boyfriend supposed to come any minute now?!” she yelled as if she had seen a ghost, and not a 21-year-old reading a book in her bed. “I’m learning Spanish, you know…” –“Ohhh Spanish! Get up immediately and clean the room! How is that guy ever going to want to marry you if he sees you lying on your bed while the room is a mess?” I tried to say something that made sense (at least in my mind): “You know grandma, Spanish is my 6th language, and marriage is not a thing I’m interested in as a 21-year-old…“. She interrupted me again: “Poor guy that has to cope with this kind of attitude and mess!”

If I were to neglect tradition, I would call this woman a masochist at worst and a sycophant at best, but not in Macedonia. In Macedonia I would call her a typical example of a woman born in the 1940s in one of the largest cities in the country. What is more, this woman is a nurse and thus holds a certain social prestige. This tradition ’not to disappoint your husband’ has been embedded in the mentality of the people for so long that today domestic violence is not even perceived as insufferable. In 2007, Macedonia, may have had 30 women in parliament, but it also had (and still has) the fourth lowest divorce rate in the world, even though media constantly reports on domestic violence. This same tradition that cherishes marriage as the greatest success condemns divorce as the biggest failure, and this cannot be changed with an electoral quota only . The Macedonian society, with an unemployment rate of 36% in 2008 and a tradition that requires women to be subordinate to their husbands, makes women inevitably the weakest link in the chain. Even if a woman decides not to tolerate domestic violence, she is most likely too financially dependent on her husband to divorce him, let alone sue him.

Moreover, the tendency to belittle women is also related to inheritance. Macedonia has the second lowest percentage in the Balkans of inherited property registered on the name of women. This not only leaves women dependent on their husband, but also on their male siblings, who inherit the property in the other 83% of the cases, as a survey conducted earlier this year reports. Both tendencies are dreadful for a society in the 21st century which de jure fights gender inequality.

Through the special public prosecutors, Katica Janeva, Fatime Fetai and Lence Ristoska, the picture that powerful women do belong in the political life of the society in Macedonia has been established. Due to the political crisis the country is currently facing, pro-government media often reduces these women to their looks, femininity and public appearance. Lastly, except for very few good examples of women present in Macedonian politics, the society lacks strong feminine figures that would lift the weight of the anchor of tradition for all women.

Through the special public prosecutors, Katica Janeva, Fatime Fetai and Lence Ristoska, the picture that powerful women do belong in the political life of the society in Macedonia has been established. Due to the political crisis the country is currently facing, pro-government media often reduces these women to their looks, femininity and public appearance. Lastly, except for very few good examples of women present in Macedonian politics, the society lacks strong feminine figures that would lift the weight of the anchor of tradition for all women.

The statistics should be improved. I cannot disagree more that women are the weakest linknin the chain, on the contrary, they hold the chain.

Both of my grandmothers were born in the 20s, they constantly reminded me that the most important thing in life is to be healthy, happy by doing what you love and be financially independent which can be achieved only by education and hard work. They also said marriage is not important as having children.

One of them had a PhD and the other one did not and yet they were on the same line on what is important in life. Because it is what their parents taught them.

Your grandmother simply was raised in a different kind of family.

One of your grandmas was born in the 1920s and got a PhD Degree? She must have been one hell of a woman, achieving a level of education as high as that, considering the fact that the number of people having a Bachelor’s Degree or higher education in liberated Macedonia after WW2 was less than 500.

If you’re going to use domestic violence as your main argument in the entire article, you need more than just assumptions, you need data, statistics or any kind of proof.

“You should get married soon” – The same is being said to men as well, Macedonia is a conservative and a relatively religious country, getting married and having children is a big expectation for both men and women.

“a tradition that requires women to be subordinate to their husbands” – What do you base this on? What part of Macedonian tradition requires, (an emphasis on requires) women to be subordinate? Which laws and regulations encourage or allow this subordination?

Also divorce laws heavily favor women in almost every western and European country.

Some of your points are good, but you need to structure your paragraphs a bit better and focus more on statistical and factual causes of sexism in culture and tradition and less on assumptions and stereotypes.